ZOOL 304

End-of-Chapter Questions

Chapter 4

Question 4.1 concerns the rate of allele-frequency change in relation to dominance.

The answer to specific problems of this sort depends on the initial allele frequency as well as on dominance.

- A dominant allele responds to selection faster at low frequency than at high.

- A recessive allele responds to selection faster at high frequency than at low.

Basically, these two statements are symmetrical. That is, both alleles necessarily change frequency at the same rate, and that rate is greater when the allele at lower frequency is dominant.

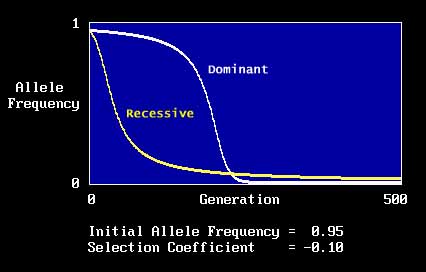

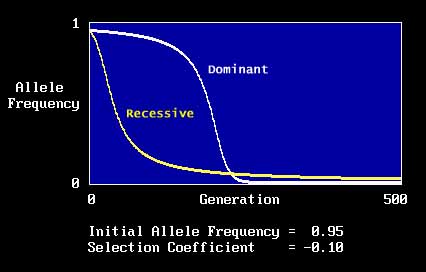

Here is a graphical representation of the two different cases described in Question 4.1 (with selection against an allele at high initial frequency).

- A recessive allele with initial frequency of 95% is shown in yellow.

- A dominant allele with initial frequency of 95% is shown in white.

Note the symmetry that can be seen by comparing the graph above with the one below.

- In the graph above, the alleles start at high frequency and are selected against.

- In the graph below, the alleles start at low frequency and respond to favorable selection.

But these are just two ways of describing exactly exact same situation. While a deleterious dominant (or recessive) allele declines (as shown above), the alternative beneficial recessive (or dominant) allele must be increasing (as shown below).

See for yourself. If you would like to explore this model of selection, by experimenting (i.e., playing) with the parameters of selection coefficient, allele frequency, and dominance and then plotting the results, send a request to Dr. King, and the program which created these graphs will be returned as an attachment. The program should run on PCs with Windows or DOS-based operating systems.

Question 4.2 asks about the relationship between heritability and genetic differences among populations. In the example, measurement showed that three populations all showed high heritability for variation in seed weight. Are we therefore justified in concluding that differences in mean seed weight are based on genetic differences?

NO.

Heritability is a peculiar statistic that relates genetic variance to total phenotypic (genetic + environmental) variance within a particular population. It applies only to the population in which it is measured. Different populations may show similarly high heritabilities (as in the example), yet their differences may be due entirely to environmental differences.

Question 4.3 asks how long it would take for a newly arisen mutant allele (presumably present in only a single individual) to reach a frequency of 95% in a population, assuming a substantial selective advantage of 10% (i.e., a selection coefficient of 0.10). The question is posed in the context of humans, with a population size of billions and a generation time of about 20 years. Could an allele frequency of 95% be reached in 1000 years (about 50 generations)?

Allele frequency responds to selection very slowly when allele frequency is low. A thousand years sounds like a long time, but for a slowly maturing species like Homo sapiens, it is a rather short interval.

Here is a graphical representation for a dominant allele, presuming a rather high initial frequency of 1 in a million (i.e., a fairly small, isolated sub-population of people, as if Chicago were surrounded by an impassable desert). For a recessive allele, the initial slow phase would be much, much longer. Novel recessive alleles depend on small populations or inbreeding to reach significant frequencies.

See for yourself. If you would like to explore this model of selection, by experimenting (i.e., playing) with the parameters of selection coefficient, allele frequency, and dominance and then plotting the results, send a request to Dr. King, and the program which created these graphs will be returned as an attachment. The program should run on PCs with Windows or DOS-based operating systems.

304 index pageNotes for chapter 1 / 2 / 3 / 4 / 5 / 6 / 7 / 8 / 9 / 10 / 11 / 12 / 13 / 14 / 15 / 16 / 17

Comments and questions: dgking@siu.edu

Department of Zoology e-mail: zoology@zoology.siu.edu

Comments and questions related to web server: webmaster@science.siu.edu