Darwin's

views were famously affected by a long (5 year) voyage

he made on board the British surveying ship H.M.S. Beagle,

where his role was officially that of upper-class companion for the captain,

Robert FitzRoy. His prior education

had been directed first toward medicine and then toward the clergy, both respectable

careers for a well-born young man. He found little attraction toward

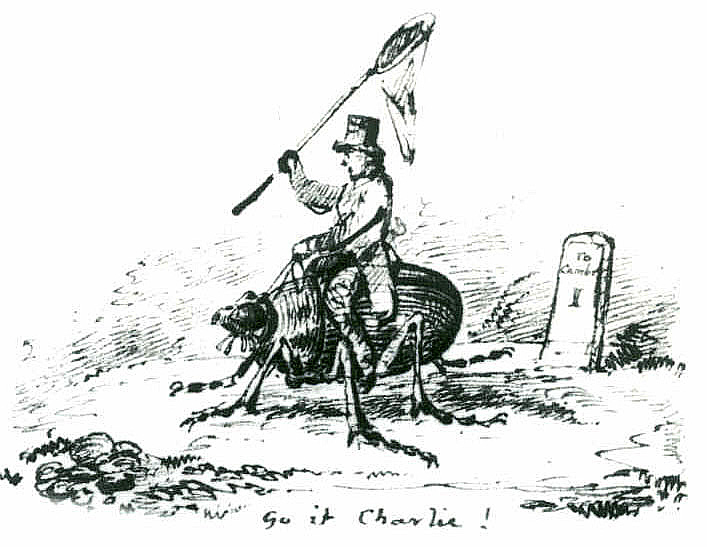

either area, but was drawn toward (or distracted by) by hunting, beetle collecting,

and natural history.

Darwin's

views were famously affected by a long (5 year) voyage

he made on board the British surveying ship H.M.S. Beagle,

where his role was officially that of upper-class companion for the captain,

Robert FitzRoy. His prior education

had been directed first toward medicine and then toward the clergy, both respectable

careers for a well-born young man. He found little attraction toward

either area, but was drawn toward (or distracted by) by hunting, beetle collecting,

and natural history.  In

some desperation, and with grave reservations, his parents sent him off on

the Beagle, to an adventure that would prove pivotal. Darwin's

popular report and travelogue on this voyage, The

Voyage of the Beagle, is a classic and enjoyable read, with fine descriptions

of life in Argentina and Chile (and other sites, more briefly) during the

early 1800s.

In

some desperation, and with grave reservations, his parents sent him off on

the Beagle, to an adventure that would prove pivotal. Darwin's

popular report and travelogue on this voyage, The

Voyage of the Beagle, is a classic and enjoyable read, with fine descriptions

of life in Argentina and Chile (and other sites, more briefly) during the

early 1800s.

By most accounts, Darwin began the voyage with rather conventional views regarding the fixity of species. But he indulged his interests (and great energy) in natural history (especially after the ship's official naturalist and surgeon resigned early in the voyage). His many observations -- on the similarities of recent fossil organisms to extant fauna in the same locale, on the similarities and differences between neighboring populations, on the types of creatures which inhabited isolated islands like the Galapagos, and on geological features and events -- all prepared him for appreciating the simple explanatory power that transformation of species over time could provide. (Lyell's uniformitanian geology provided the conceptual basis for appreciating how small changes could accumulate over time. Darwin had the fortune to experience a severe earthquake in Chile, which elevated the shore by several feet. He easily extrapolated that observation into an explanation for marine sediments seen high in the Andes mountains.)

Darwin's

Autobiography

explains how he spent the twenty-three years between his return and publication

of the Origin. Notably he credits his reading of Thomas

Robert Malthus' "An essay on the principle of population" as the stimulus

for understanding how natural selection could operate. In 1858 Darwin

received a manuscript from Alfred Russel Wallace,

"On the tendency of varieties to depart indefinitely from the original type"

which, Darwin writes, "contained exactly the same theory of mine." Wallace

sometimes receives joint billing with Darwin as co-discoverer of natural selection.

But the overwhelming credit generally given to Darwin is fully justified

by Darwin's well-documented writings over many years before Wallace's essay,

and by the much greater depth and thoroughness of Darwin's account in his

Origin.

Darwin's

Autobiography

explains how he spent the twenty-three years between his return and publication

of the Origin. Notably he credits his reading of Thomas

Robert Malthus' "An essay on the principle of population" as the stimulus

for understanding how natural selection could operate. In 1858 Darwin

received a manuscript from Alfred Russel Wallace,

"On the tendency of varieties to depart indefinitely from the original type"

which, Darwin writes, "contained exactly the same theory of mine." Wallace

sometimes receives joint billing with Darwin as co-discoverer of natural selection.

But the overwhelming credit generally given to Darwin is fully justified

by Darwin's well-documented writings over many years before Wallace's essay,

and by the much greater depth and thoroughness of Darwin's account in his

Origin.

The decades between the publication of Darwin's Origin of Species and the establishment of the Modern Synthesis in the 1930s saw a complex struggle among scientific ideas, difficult to compress into a brief introductory lecture. See the books by Moore, by Mayr, and by Eiseley, listed under References below, for very readable elaborations. Some of the earliest objections were based on poor understanding or incredulity. In a letter to Lyell, Darwin writes of one critic (Richard Owen), "He added another objection, that the book...explained everything, and that it was improbable in the highest degree that I should succeed at this. I quite agree with this rather queer objection, and it comes to this that my book must be very bad or very good." During the period immediately after publication of the Origin, when Darwin's ideas were still startling and unfamiliar, Thomas Henry Huxley earned a lasting reputation as "Darwin's bulldog", promoting, popularizing, debating and defending the new concept of evolution by natural selection.

After a short initial shock, the idea of descent with modification was quickly accepted by much of the scientific world. However, there were holdouts. The idea of the fixity of species, associated with the idea of underlying immutable types created by God, exerted a powerful influence which continues to this day. (Even in biology, the typological species concept remains widely used.) Lyell, the great geologist who inspired Darwin, was won over only after much effort by Darwin. Among the prominent figures who never did accept evolution were Louis Agassiz, famous for correctly interpreting geological evidence of continental glaciation during the the ice ages and for work with fossil fishes, and the great comparative anatomist Richard Owen, who coined the terms "dinosaur" and "homology". Nevertheless, the basic concept of descent with modification was widely accepted.

Exploring the implications of descent with modification became a great goal for biology. The term homology was redefined to mean similarity based on derivation with modification from the form of a common ancestor. (Previously, the term homology as coined by Owen had referred to similarity to an archetypal form.) Research in paleontology, comparative anatomy and embryology led to the accumulation of vast amounts of data in support of evolution. Discovery of new fossils, such as Archeopteryx, provided dramatic confirmation of evolutionary ideas.

However, Darwin's essential idea of natural selection as the mechanism driving evolution did not fare nearly so well. Many who understood the concept of natural selection could appreciate how selection could necessarily eliminate the unfit without being convinced that selection could also create the fit. Darwin muddled things himself with unsatisfactory genetic speculations in later editions of the Origin. In the absence of any satisfactory theory of genetics, the basic mechanism could not be properly understood. Many traits appear to blend during a cross (children often look more-or-less like a mix of both parents), and blending inheritance appears inconsistent with preservation of novel mutations. Ironically, Gregor Mendel published his famous experiments with pea hybrids shortly after Darwin's Origin, but the value of that work remained unrecognized until the twentieth century. A further difficulty was introduced by August Weismann's evidence (for higher animals, at least) of germ cell segregation, strongly implying that acquired characters could not be inherited. This effectively eliminated one obvious source for heritable variation (not only Lamarck, but also Darwin himself, considered that acquired characteristics might be inherited).

Adding to this difficulty was the intuitive implausibility of macroevolutionary transformation (e.g, fish to bird, kangaroo or elephant) by a slow, gradual process of change. St. George Jackson Mivart advanced the influential idea (still supported by creationists) that certain complex structures, such as the wings of birds, could not be built by natural selection because in their initial, incipient stages they would not be advantageous and would often be disadvantageous.

Another problem was the occurrence of evolutionary trends in the fossil record (such as repeated long-term increases, or decreases, in body size within a lineage) which seemed to transcend simple adaptation. Orthogenesis, the idea that trends were driven along certain lines by some (unexplained) internal or external force, provided an alternative to natural selection.

Throughout this period, the idea that evolution reflected some inherent progress or improvement of life became deeply established. This idea of progress represents a transference onto evolution of ideas appropriate for the old Scala Naturae or "Great Chain of Being" world view, little altered by the radically different context. We still speak glibly of "higher" and "lower" animals, of "primitive" and "advanced" traits, although such terms are quite inappropriate in Darwin's scheme and can be downright misleading.

A completely different sort of scientific objection came from physics, where the the new quantitative tools of thermodynamics could be used to calculate the age of the sun and the earth. Basically, even if the sun were fortuitously composed of a fuel as efficient as coal, even such a huge sphere must eventually burn out. Internal heat of the earth was presumed to be left over from that generated by gravitational collapse when the earth first formed, which could be calculated; then rates of heat loss could be measured and a maximum age for the earth derived, before it cooled completely to a solid ball. Such various and independent arguments, notably by William Thomson, Lord Kelvin, led to the conclusion that the earth could not be more than a few million years old, very old to be sure (relative to estimates, based on scripture, of a few thousand years) but an uncomfortably short time for evolution by the creepingly slow process that Darwin had envisioned. These arguments were troubling, but vanished as soon as the hidden energies of the atom were discovered. The earth's is constantly heated by radioactive decay, and the Sun's prodigious energy output derives from not from chemical combustion but from conversion of mass to energy.

A very curious chapter in the history of evolution began with the rediscovery of Mendel's laws at the beginning of the twentieth century. Eventually Mendelism was understood to provide an explanation of heredity that was consistent with the requirements of evolutionary theory. However, experimental genetics first revealed mutation to be a sudden, all-or-nothing process. This led to a widely accepted view, called mutationism or saltationism, that transmutation of species occurred suddenly, determined entirely by the mutational process, rather than as a gradual process guided by natural selection. Far from being seen as a validation of Darwinism, for a couple decades Mendelism was widely viewed as providing conclusive refutation of Darwinian evolution.

Our modern view of evolution began when the principles of Mendelian genetics were combined statistical population genetics, together with the realization that mutations could have small effects as well as large. The result was the Modern Synthesis, also sometimes called neo-Darwinism. Key names in the establishment of the Synthesis, during the late 20s, 30s, and 40s of the Twentieth Century, are:

Take note of these names. You shall encounter them again if you pursue studies in evolution or population biology.